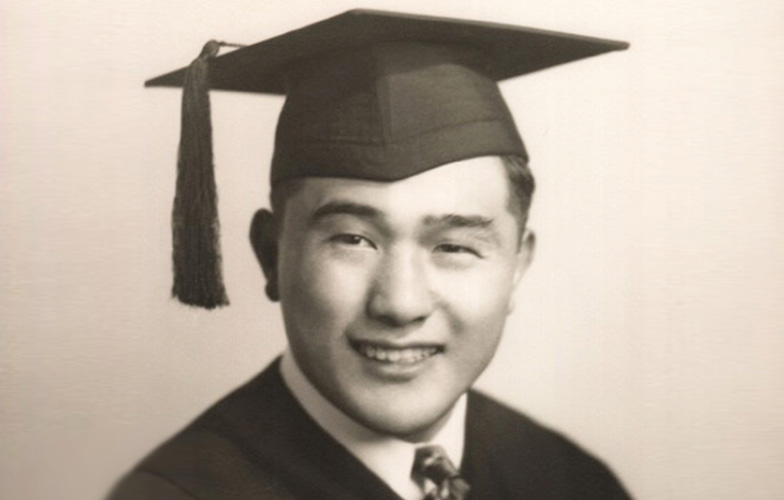

For those of us that know him, it is hard to imagine Mr. Uchida as a beginner judoka. Yet, there was a time when Yoshihiro Uchida tied his first white belt and enrolled in his first judo class at the age of 10. “My parents thought that my brother and I didn’t have enough knowledge of our Japanese culture so they thought judo was something that would be good for us.” He and his younger brother George began their judo education in a small dojo in Southern California called Stanton. They took their falls on “sawdust and canvas,” and wore a gi that looked very similar to the ones we wear today.

Uchida learned quickly and worked diligently. He started classes at SJSU and began teaching judo in a small classroom, but was interrupted by a draft letter from the army that told him to report for service in 1942. During his time in the army, Uchida served as a medical technician in several Forts across the country, and learned many skills that helped him with his medical lab business in his later years.

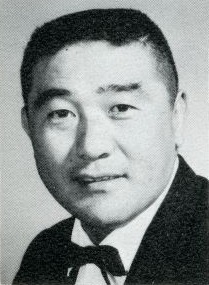

Uchida recalls that one of the biggest challenges upon his return from the war was finding a job. Many work environments were hostile towards Japanese-Americans after the war. In 1946, he returned to SJSU to teach his first judo class at the University. It was beginner’s level judo and was classified as a self-defense class. “I was one of the first and only Asians hired in that era at SJSU. The dojo was in YUH 6, right across the hall from the gym, where they store all the wrestling and gymnastics stuff. Now I guess it’s gone and under construction, but the SJSU dojo has been in that building since the beginning.” His first students were WWII veterans who had experienced the wear and tear of both the Pacific and European warfare. With time, they began to respect Uchida for his knowledge of judo and his strong character.

After setting the foundation for SJSU Judo, Uchida’s next project was to create the weight system. Today, judo is divided into seven weight classes for women and men; however, in Uchida’s day this did not exist. The philosophy behind judo was that a small man could defeat a big man with diligent study and fighting spirit. However, as Judo became more popular, it became important to ensure the safety of the judoka. Walking the line between Martial Art and competitive sport, Uchida and a few other men decided to make judo equal and fair. At that time, they held a tournament and decided on dividing the weights into 130 lb., 150 lb., 180lb., and heavy weight; the winner of each category would fight the winner of another until a single grand champion was named. “Not everyone was happy. The die-hard judo people said that judo is not for weights. In Japan, they have the smallest guys against the big guys, and they have the All-Japan Championships. But these weight categories were necessary to make judo fair.” It wasn’t until later in the 1960s that Europeans took out the grand champions and honored the champions of each category individually.

The establishment of the weight system coincided with the first Collegiate Championships. The NCJA was formed in 1953 and Colorado Springs held the first National Collegiate Championships in 1962. Uchida, with a smile, will often point out that “since then we’ve won almost all of them.”

Uchida is also responsible for helping establish the Palo Alto and San Jose Buddhist Judo clubs. Working with the local founders Don “Moon” Kikuchi, Sam Hamae, and Tom Kitaura, Uchida saw an opportunity to give the young Japanese Americans returning from internment camps something like judo; it would give them “courage and confidence” to face adversity as well as diversity.

Through coaching, Uchida has seen his students become champions and obtain successful careers. In 1964, Uchida coached the first US Olympic Judo team in Tokyo. He said, “It was the first Olympics, so everyone thought you were great. I didn’t think like that, but it was the honor, knowing you contributed to something so great.” As time progressed, more champions arose. And every four years SJSU would support a few more aspiring athletes. Uchida never coached at the Olympics again, but he was the Assistant Director of Judo at the Los Angeles Olympics. The legacy of Olympic Judo at SJSU continues to flourish—most recently, Uchida proudly watched SJSU alum Malloy capture the bronze medal at the London Games. “Marti’s win was very exciting, especially because of her comeback. And later that night, she honored me with my favorite award to this day, the ECOS Award. And to be given that by an Olympian, it’s a great honor.” After an Olympian has medalled, he or she gives the ECOS award to someone who not only coached and supported the individual but also offered wisdom and guidance on the journey to the Games. Marti gave this award to Uchida the night of her win, and it sits on his desk today right where he can see it.

The SJSU judo program has flourished under Uchida’s leadership and he welcomes all his guests with great hospitality. Because of his legacy, SJSU judo has had the privilege of training with international athletes from Japan, Mexico, Spain, Brazil, Israel, Kuwait, Canada, and Germany, and in doing so passes on his spirit of learning and sharing judo with the community. However, he stresses the importance of education just as much as judo. He cares about your GPA just as much as your newaza technique. For Uchida, judo and education are the building blocks for strong, confident, and successful young individuals. “Our students learn to think critically, too. People learn to see that not everything is true in the world and realize that they can screen these things out. They are not only hard workers but intelligent and I am proud of that.” All that Uchida tries to teach his students, he has learned through personal experience and time. Uchida tries to teach more than just judo—he tries to teach confidence. He teaches that with good character it is possible to come from a humble background and thrive.

“Over time, they graduate and they find confidence. They will have the physical confidence in themselves and with the academic background they can stand up and say things. Things that they believe in.”